'Poisoning the blood': How hatred of immigrants festered and metastasized

Eliminationism in America, Part 12: How nativism begat the radical right's most successful recruitment and radicalization campaign by ginning up fear and loathing of Latinos.

Part 12 of 15: [Parts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11.]

It was a classic media circus: TV crews and newspaper photographers out on the desert borderlands, crowded around the small cluster of border watchers, vying for a chance to interview the handful of participants, dutifully recording the bellicose warnings of their leaders regarding the dangers of illegal immigration. You could count eight times as many journalists as vigilantes.

The year was 1977, and it was the first organized anti-immigrant border watch. The leaders: David Duke and his revived Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

At the time, Duke was riding the crest of a wave of media attention. He had first made headlines in the early 1970s by protesting on Louisiana campuses dressed in Nazi garb and then declaring himself the business-suited new face of a revamped Klan, scrubbed and polished for modern consumption. He was featured in segments on 60 Minutes and appeared on Tom Snyder’s Tomorrow show after challenging Snyder—who had blasted Duke publicly—to let him have his say. Afterward, Duke crowed: “We bested Tom Snyder. The show gave me national exposure and made it much easier to get my ideals across to many more people. And that’s what it’s all about.”

The idea of an anti-immigration border watch was actually hatched by Duke’s Klan lieutenant in California, another ex-neo-Nazi named Tom Metzger. But following in the wake of other successful publicity stunts by the Klan, Duke seized on the idea and made it into another media event.

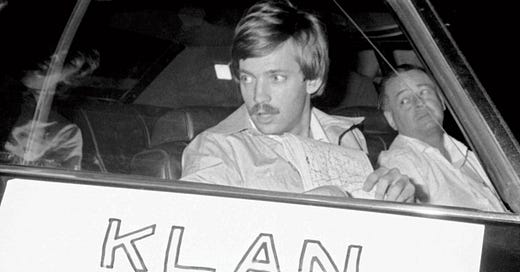

He arrived in California to great media fanfare on October 16, 1977, at the immigration offices on the US border crossing at San Ysidro, California. Surrounded by a small phalanx of Klansmen, Duke had toured the facility while outside a large crowd of antiracist protesters threw rocks and eggs.

Asked to explain his purpose, Duke said, “We believe very strongly white people are becoming second-class citizens. When I think of America, I think of a white country.”

In Sacramento a few days later, he held a press conference announcing a “Klan Border Watch” that would supposedly enlist somewhere between five hundred and a thousand Klansmen in a vigilante patrol stretching from Texas to California. Again, he was met by a large crowd of protesters. The ensuing scenes attracted more press attention, so that by the day of the event, national and state media alike were flocking to cover it.

On October 25, the border-watching contingent arrived at their announced site—the border crossing near the town of Dulzura in rural San Diego County—in three sedans with hand-painted “Klan Border Watch” signs attached to the sides. When they emerged, Duke was accompanied by a small cluster of Klansmen; all told, his contingent comprised seven people—massively outnumbered by the press corps alone, not to mention the large crowd of protesters also drawn to the site.

Duke spent the day either being interviewed by reporters or talking on a citizens’ band radio, supposedly relaying information about border-crosser sightings, provided by the “hundreds” of Klansmen he claimed were participating, to eagerly awaiting federal agents. Duke announced that the information had produced “thousands” of arrests. Most of the media reported his claims dutifully—even though it shortly emerged that in fact there had been no increase in border-crossing arrests that day.

Duke later mused for readers of his Klan paper, The Crusader, on how easy it had all been: “When a hundred reporters are gathered around hanging on every word, when they help you accomplish your objectives by their own misguided sensationalism, if indeed it was a media stunt, it was by their own presence an admission that it was a very brilliant one,” he said.

The die had been cast. Thirty years later, right-wing extremists would follow Duke’s blueprint to perfection, but without the stigma of the KKK association. Instead, the compliant press would depict them as ordinary Americans.

***

During the 1980s and ‘90s, far-right extremists remained intent on returning to a preeminent cultural and political position within the mainstream, but they shifted their strategy. Instead of trying to reshape public perceptions about their organizational entities like the Klan, they chose to downplay, deny, and disguise their racist and antisemitic beliefs, and instead follow the path of their Nativist forebears: wrap themselves in patriotic bunting, emphasize pseudo-patriotic rhetoric about the Constitution, and generate recruitment through conspiracist, often paranoid claims about concocted enemies like the New World Order and other variations of the hoary “communist cabal controls the world” narrative. They called themselves the “Patriot movement.”

They also adopted an internal strategy called “leaderless resistance,” which would assign the work of violent opposition to individuals and smaller, mostly localized cells of operation that would free the movement’s leaders from culpability for the actions they were urging their followers to take. Thus, the Patriot movement’s chief strategy revolved around forming citizen militias—and indeed, as the movement gained traction and attracted media attention, it became largely known as the “militia movement.” Militia cells formed in every state of the union, all of them independent entities, all of them working toward the same, anti–New World Order agenda. They often had their own regional orientation: in the Northwest, militias were typically expressions of anti-environmental backlash; in Alaska, they revolved around efforts at seceding from the Union; in places like Michigan and Florida and Alabama, the paranoia was all about gun ownership.

But the issue of illegal immigration had remained a staple of the Patriot agenda, so in border states, particularly Arizona, California, and Texas, the focus was firmly on stanching the flow of Hispanic immigrants into their states. Border militias became popular for these Patriots, along with the usual mix of conspiracy theories and ethnic fearmongering.

The most prominent of these border-militia Patriots was a retired California businessman named Glenn Spencer. Beginning in 1992, Spencer’s original organization, Voices of Citizens Together, worked tirelessly to stop the flow of Hispanic immigrants into the country. VCT was a leading proponent of the 1994 California initiative to deny educational, health, and other benefits to undocumented immigrants and their children, Proposition 187 (which was approved by voters but later invalidated by the courts).

In 1995, Spencer began spreading his message through a strong Web presence, particularly his site, American Patrol. Much of its news was dedicated to reporting on crimes committed by Latinos, as evidence connecting immigration with criminal activity. But there was also a steady theme: Spencer picked up the old Klan Border Watch concept and repackaged it by promoting the idea of border militias, along with the usual panoply of New World Order conspiracy theories. American Patrol was rife with openly bigoted contempt aimed at Latinos, embodied in the cartoon that depicted a character urinating on a picture of a prominent Latino activist. Spencer also penned missives to other publications, including a 1996 letter to the Los Angeles Times claiming that “the Mexican culture is based on deceit. Chicanos and Mexicanos lie as a means of survival.”

Besides border militias, Spencer became devoted to his own pet conspiracy theory, promoted on the American Patrol website, in his newsletter, and on his radio show: namely, that a cadre of Latino radicals, in conjunction with the Mexican government, was conspiring to take back the American Southwest by invading the region with hordes of immigrants and then reclaim it for Mexico as part of a greater nation called Aztlan. It became known as the Reconquista theory, a name from Spanish history that Spencer requisitioned for his own purposes. The basis of the theory is a set of obscure documents written by Chicano activists in the late 1960s calling for a reimagined America. Some of these manifestoes were associated with the founding of the student Latino organization Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan, better known as MEChA. Moreover, the MEChA constitution’s preamble calls for the “self-determination of the Chicana/Chicano people and the liberation of Aztlan.”

In Spencer’s retelling, an idea aimed at multicultural solidarity was transformed into a racist and exclusionist enterprise, and an organization betterknown for bake sales and campus socials became the equivalent of the Ku Klux Klan. MEChA, Spencer claimed, was fundamentally racist. As early as October 1996 he was running articles with titles like “MEChA calls for the Liberation of ‘Aztlan,’” which warned: “Those who scoff at the idea of a Mexican takeover of the Southwestern United States don’t understand history and they underestimate the Mexicans.”

American Patrol continued to make a fetish out of the Reconquista theory and MEChA in subsequent years, embodied by the section devoted to what it called “The Scourge of MEChA,” not to mention the running coverage of anything it could attribute to the Aztlan takeover. Spencer himself became so devoted to his theory that in 2001 he had a copy of his videotape, Bonds of Our Nations—which lays out the Reconquista plans in graphic detail—hand-delivered to every member of Congress. The woman making the delivery was Betina McCann, the fiancée of a notorious neo- Nazi named Steven Barry.

Eventually Spencer’s theory made it into mainstream media via the right-wing blogosphere. In August 2003 bloggers Michelle Malkin and Glenn “Instapundit” Reynolds, in an effort to harm the California gubernatorial candidacy of Latino politician Cruz Bustamante, picked up Spencer’s claims about MEChA whole off his web postings and began running them credulously, claiming that MEChA was a racist organization of. scheming, America-hating radicals. Reynolds went so far as to attack MEChA members as “fascist hatemongers.” On Fox News, Bill O’Reilly and his fellow hosts repeated the claim and accused Bustamante, a former MEChA member, of dallying with racists. Bustamante wound up a distant second to Arnold Schwarzenegger in the election.

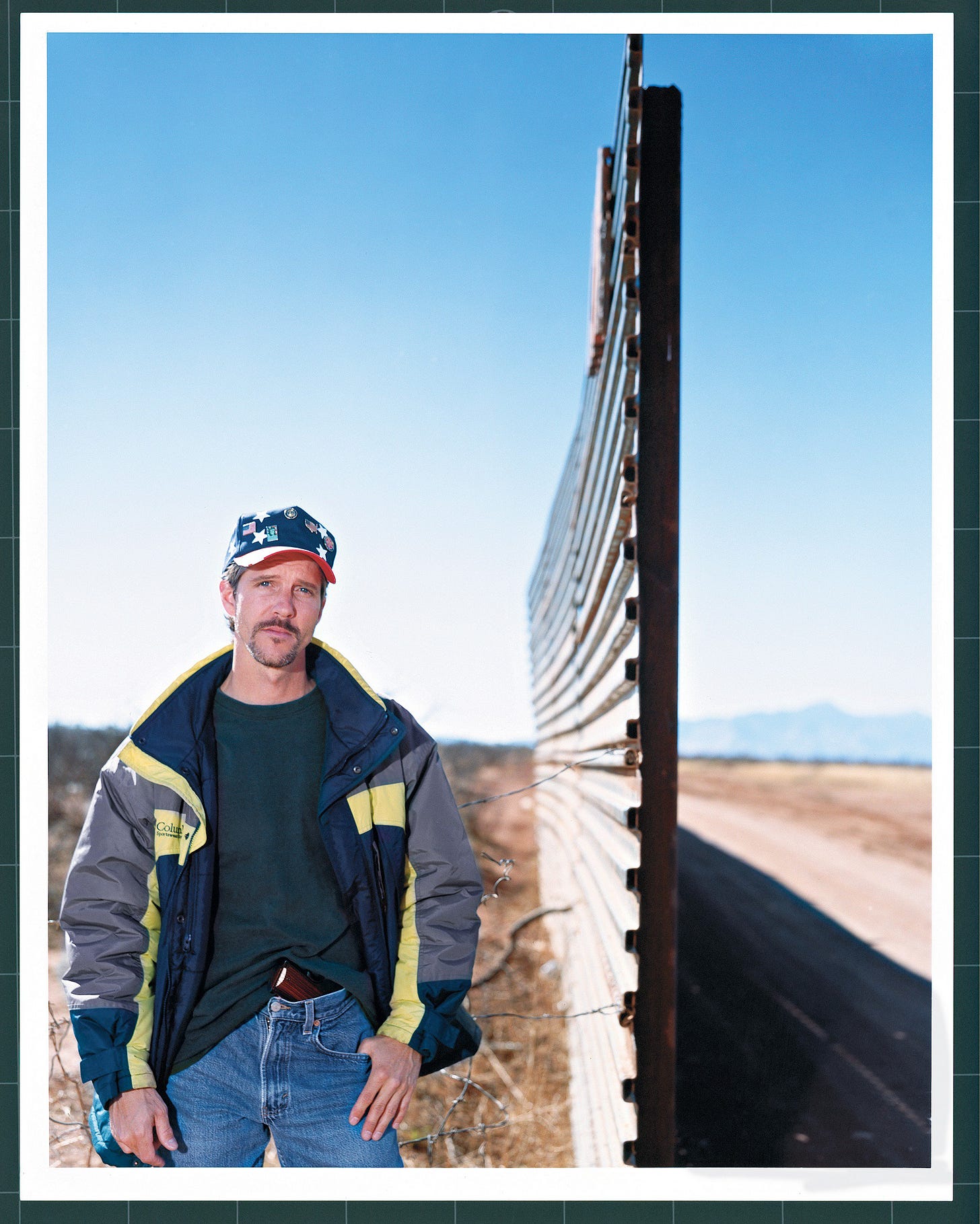

By then, Spencer had moved from California to Arizona and expanded his operations, buying a large ranch not far from the border and setting up watches for crossers on his land. He had been drawn there by a number of other ranchers who were becoming angry about the volumes of immigrants crossing their properties and had decided to take matters into their own hands. And he brought with him his penchant for hateful, bigoted and profoundly eliminationist rhetoric.

On the ground level, this rhetoric naturally gained an audience with Glenn Spencer’s crowd. Roger Barnett was an Arizona rancher who worked some twenty-two thousand acres—most of it leased federal land—near Sierra Vista and Douglas. He was profiled in 2000 by Time magazine’s Tim McGirk, for whom Barnett was emblematic of how “anger against the growing flood of 1 million illegal immigrants a year is rising fast among independent-spirited, gun-toting residents in the borderlands of Arizona, Texas and New Mexico.”

McGirk described Barnett’s methods of dealing with border crossers:

With his binoculars, an M-16 automatic rifle and his sheepdog Mikey, Barnett sometimes tracks a group of illegals for miles, following their footprints in the sand and bits of clothing snagged on the mesquite thorns. In the summer it’s harder for his dog to track them; the incandescent heat sears away their scent. “They move across the desert like a centipede, 40 or 50 people at a time,” says Barnett. Once he catches them, Barnett radios the border patrol to cart them off his land. “You always get one or two that are defiant,” says Barnett, who chuckles, remembering an incident a few weeks back. “One fellow tried to get up and walk away, saying we’re not Immigration. So I slammed him back down and took his photo. ‘Why’d you do that?’ the illegal says, all surprised. ‘Because we want you to go home with a before picture and an after picture—that is, after we beat the s___ outta you.’ You can bet he started behavin’ then.”

This kind of violent talk and threatening demeanor became the standard mode of operation for the “citizen border watch” organizers who followed in Barnett’s wake. Indeed, the border watchers’ rhetoric so starkly dehumanized and demonized Latinos that their similarity to hate groups became inescapable. Perhaps that was because it was attracting white supremacists to their cause.

In May 2000, Glenn Spencer and his Proposition 187 cohort, Barbara Coe of the nativist California Coalition for Immigration Reform, cosponsored a public gathering in Sierra Vista revolving around Roger Barnett and the rising border issues. Also in attendance were two members of David Duke’s organization, the National Organization For European American

Rights (NOFEAR), and two members of an Arkansas Klan group—though of course Spencer and his local cosponsors all claimed they were unaware of their presence.

The rhetoric was in keeping with such an audience, however. In her speech to the gathering, Coe declared that government border policies were an abject failure that had forced ranchers to “defend our borders and defend themselves from illegal alien savages who kill their livestock, and slit their watchdogs’ throats . . . burglarize their homes and threaten the physical safety of their loved ones.”

The gathering inspired the formation of one of the first and most prominent border militias, an outfit called Ranch Rescue that was run by a Texas man named Torre John “Jack” Foote. It claimed chapters in all the southern border states and Colorado as well. Foote explained in a 2003 interview with the white-supremacist website Stormfront that Ranch Rescue’s first “field mission” took place in October 2000 on Barnett’s ranch and that it had become intensively active ever since: “We’re still seeing hordes—mobs—of criminal aliens pour across this privately-owned property, and the best thing we can expect from our own government is that they will do everything possible to aid the pro-criminal alien groups.”

That first operation advertised for recruits by calling for would-be border watchers to “come have fun in the sun” while volunteers hunted “hordes of criminal aliens.” Men with military and weapons training were preferred. Recruits were urged to bring their RVs, guard dogs, and trained attack dogs. Once on site, volunteers were given dire instructions warning of various lethal threats to their well-being, urging them to do whatever they needed to protect themselves. On patrol, they equipped themselves with an assortment of weapons, including high-powered assault rifles, as well as night-vision devices, two-way radios, flares, machetes, and all-terrain vehicles.

When accused of harboring racist motives, Foote responded with a peculiarly vehement bigotry: “You and the vast majority of your fellow dog turds are ignorant, uneducated, and desperate for a life in a decent nation because the one you live in is nothing but a pile of dog shit made up of millions of worthless little dog turds like yourself,” Foote wrote to a Mexican American who accused him of racism. “You stand around your entire lives, whining about how bad things are in your dog of a nation, waiting for the dog to stick its ass under our fence and shit each one of you into our back yards.”

In March 2002, Foote and another ex-Californian, Casey Nethercott, set up a border watch on the Texas ranch of a member named Joe Sutton and dubbed it Operation Falcon. The idea was to use the Sutton ranch as a base for hunting illegal border crossers. That was when everything started to turn sideways for Ranch Rescue.

Nethercott already had quite the track record. A big blond man, he had made his living for a few years in California as a bounty hunter but had run afoul of the law when he wrongly apprehended the son of the chief of police in Riverside. He wound up serving prison time for felony assault and false imprisonment. He had therefore lost the legal right to carry a gun—but of course, he owned and used several as part of his Ranch Rescue work.

On March 18, 2002, two would-be immigrants from El Salvador named Fatima Leiva and Edwin Mancia made the mistake of crossing the Suttons’ ranch in the early morning hours and found themselves confronted by Ranch Rescue members, who chased them into the brush. Joe Sutton himself reportedly fired numerous gunshots in their direction, shouting obscenities and threatening to kill them. Eventually they were sniffed out by Casey Nethercott’s Rottweiler and yanked from the brush; Mancia was ordered to stand up and then was struck in the back of the head with a handgun.

While he lay on the ground, Nethercott allowed the Rottweiler to attack Mancia, ripping his sweatshirt. The pair were interrogated and accused of being drug smugglers. After enduring an hour and a half of such abuse, they were handed over to authorities. They promptly filed criminal complaints against Nethercott and one of the other border watchers. Nethercott was also charged with a weapons violation for possessing a gun. The lawsuits followed a year later. The whole gang from Joe Sutton’s ranch—including Jack Foote and Casey Nethercott—was sued the next June for civil rights violations by the two Salvadoran immigrants, represented by the Southern Poverty Law Center and the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

But Nethercott was just getting started. In early 2003, he purchased a seventy-acre ranch not far from Roger Barnett’s in Cochise County, Arizona, and he promptly began converting it into an armed compound. He called it Camp Thunderbird. His neighbors were furious and filed numerous complaints against Nethercott for violating various county land-use ordinances.

Glenn Spencer was already a neighbor, by a matter of months. In September 2002, he announced he had given up on California: “California is a lawless, lost state,” he told reporters. “There’s nothing I can do for California. It is finished.” Spencer also recommended white flight: “White Americans should get out of California—now, before it is too late to salvage the equity they have in their homes and the value of their businesses.” He bought a property in an exclusive Cochise County neighborhood and set up his revamped American Border Patrol (ABP) organization there, with an assist from Roger Barnett and his friends, who introduced Spencer around to the locals, particularly the county’s law enforcement officers.

Things turned rocky in August 2003, when Spencer shot up a neighbor’s garage with a .357 rifle after hearing “suspicious” noises in his backyard. He eventually pleaded guilty to reckless endangerment and was fined $2,500 and given a year’s probation. In the meantime, his upscale neighbors at Pueblo del Sol slapped him with a complaint for running his business from his home—which violated several of the subdivision’s covenants. So he gave up and moved his operation to another location.

Spencer’s plan was different from the others: his ABP was more of a high-tech affair, in contrast to his fellow border watchers’ boots-on-the-ground approach. Spencer and his volunteers operated remote-controlled airplanes equipped with cameras and other monitoring equipment, and he flew his own Cessna over border areas with similar equipment. He also sent out volunteer “hawkeyes” to monitor border crossers’ movements with video cameras and other high-tech equipment.

Casey Nethercott, however, favored the border-militia approach that Spencer had advocated previously. He and his Ranch Rescue cohorts built a base of operations at Camp Thunderbird, outside of Douglas, Arizona, that was a militiaman’s dream: watchtowers, bunkers, barracks, a helicopter landing pad, an indoor firing range. In November 2003, his neighbors filed two complaints about the work, alleging various zoning violations.

It was kind of a bad month for Nethercott: On the thirteenth, FBI agents came out to the Douglas ranch and arrested him as fugitive for having fled the weapons charge in Texas. Jack Foote told reporters that Nethercott’s lawyer was trying to get the weapons charges dropped. In the meantime, he said, he and his volunteers were busy building a home base for Ranch Rescue.

Their activities created fears that not only might they inflict violence on hapless border crossers, but at some point they could create an international incident—especially since they had begun to threaten the Mexican military with violence should any of its soldiers wander over the border, as was known to happen from time to time. In February 2004, Foote issued a warning that the next time a Mexican soldier set foot on their ranch, he would be fired on: “Two in the chest and one in the head,” he said.

Douglas’s mayor, Ray Borane, worried that they would create a cross-border shootout: “This isn’t a game,” he said. “That’s the thing that has always worried me, that these people would cause an international incident and not only hinder relations with Mexico, but that they’d make this area become a hotbed for other organizations like that.”

Over the next few months, though, Foote and Nethercott had a falling-out, and by April, the Douglas ranch was no longer the home base for Ranch Rescue. Instead, in spring 2004 Nethercott announced he was starting up a border-watch group of his own called the Arizona Guard, which its website described as “an Organized Militia dedicated to the defense of American Patriotism and to help local ranchers and citizens defend property from illegal alien activity and drug running operations.”

His new recruitment chief was Kalen Riddle, a twenty-two-year-old from Aberdeen, Washington. On his own website, Riddle declared himself a “National Socialist” and ran pictures of himself in Nazi uniform, embellished with swastika armbands, brandishing a rifle. Two of his favorite things, he declared, are “ethnic cleansing and weapon making.” Riddle requested that “any WN [White Nationalist] volunteer is asked to keep WP [White Power] or Third Reich imagry (sic) to a minimum and not to talk to any press.”

Nethercott denied that anyone in his organization was a Nazi. “When words come up like hate, white supremacy and Nazism, and genocide, those are words that are made for people to inflame people,” he said in a local radio interview. “None of those apply to us.”

On August 31, 2004, three Border Patrol agents tried to pull Nethercott over as part of a smuggling investigation. Instead of cooperating, he took them on a long, slow-speed chase to his ranch, where he got out at the gate and phoned inside for help. The Patrol officers claimed he threatened them with assault and attempted to intimidate them, but they drove away at the end of the tense standoff.

A couple of weeks later, Nethercott was pulled over in a Safeway parking lot in Douglas by FBI agents, intent on arresting him on charges of assaulting a federal officer. Kalen Riddle was with him, and he was armed. During the arrest, an agent said he saw Riddle make a move toward his waist, so he shot him. Riddle was critically injured and spent several weeks recovering in a hospital. Casey Nethercott was hauled off and jailed on the assault charge. He remained there for five months, but he was later acquitted of the assault

charge. (Eventually Nethercott would serve nearly five years in prison for the felony weapons-possession charge in Texas.)

Jack Foote told a local TV reporter that he and Ranch Rescue had severed their ties with Nethercott back in April over his increasingly evident racial views. “We’re all better off with Nethercott in a cage, welded shut,” Foote sneered.

Within the year, however, Ranch Rescue was finished—especially after the courts ruled in favor of the two Salvadoran emigrants, Fatima Leiva and Edwin Mancia. With the help of their SPLC attorneys, the pair obtained judgments totaling $1 million against Foote and Nethercott. They also obtained a $100,000 out-of-court settlement from Joe Sutton. In August 2005, Casey Nethercott’s Douglas ranch was seized and deeded to the Salvadorans. Camp Thunderbird became an ordinary ranch in the desert again. Jack Foote closed up the Ranch Rescue shop and shut down its website.

But by then, they had become yesterday’s news. The shiny new border watch on the block—calling themselves the Minutemen—had become the latest media darling.

***

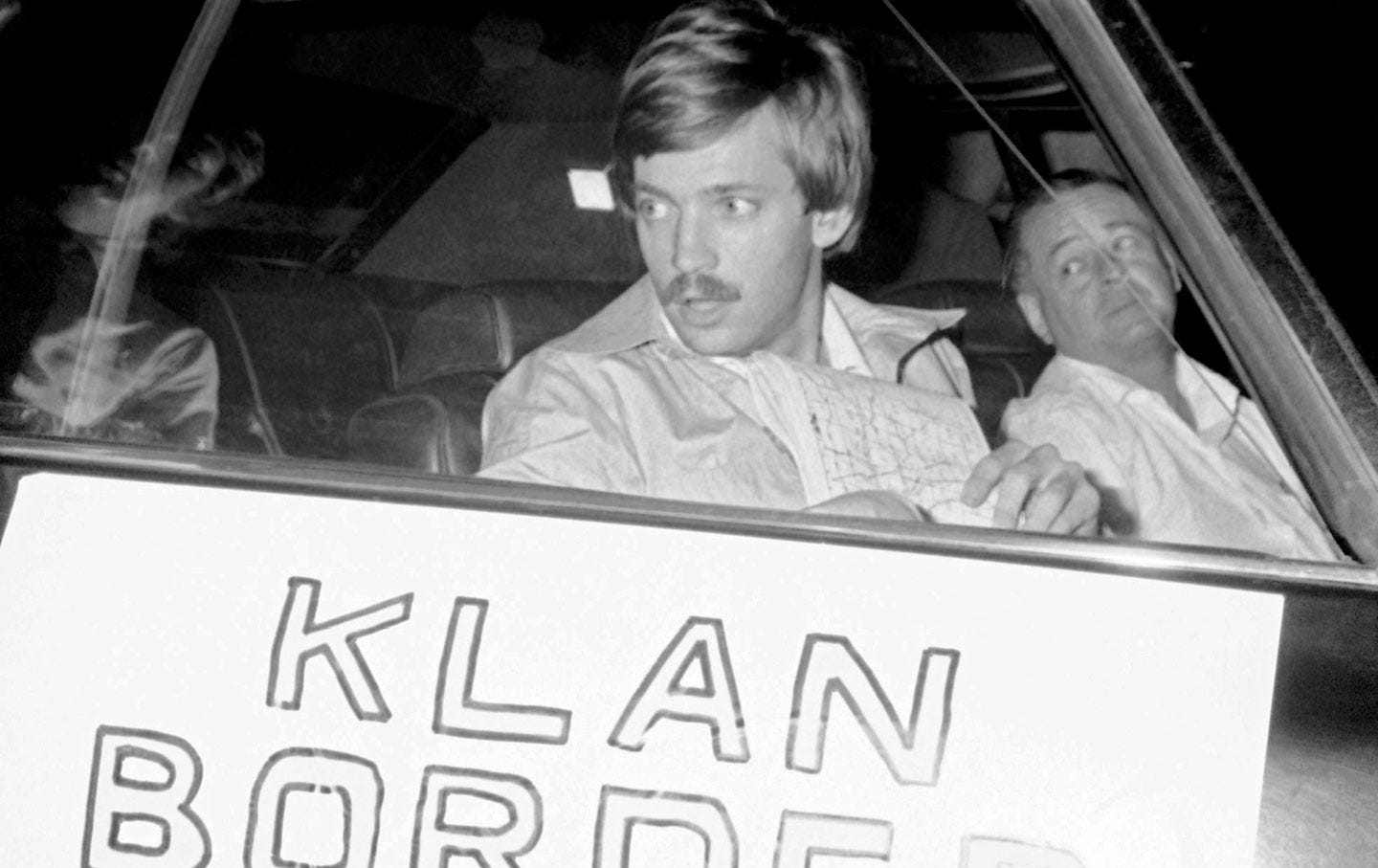

Chris Simcox liked to pose for the media with a pistol down the front of his pants. In certain video appearances, too, when he was first attracting attention, you could see him shove his handgun under the front waistband of his blue jeans. He probably thought it made him look like a devil-may-care Western outlaw type. Of course, all it really did was brand him the outsider, the clueless city dude from California he always was in his adopted Arizona hometown.

When Chris Simcox first arrived in Tombstone in 2002, he found work as one of the actors in the town’s daily reenactment of the mythos-laden Gunfight at the OK Corral. It was a way of staying afloat until he could get his feet on the ground. He had been drawn by the myth, and now he was on a mission to transform it into a kind of living reality.

A few months before, he had thrown away his previous life as a schoolteacher in California, moved out to the Arizona desert, and had an epiphany, all because of the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, DC, on September 11, 2001. Traumatized by repeatedly watching the collapse of the Twin Towers, Simcox had sold off his belongings and moved out to camp in the Sonoran desert, where he witnessed all kinds of human and drug trafficking— or so he was fond of repeatedly telling reporters in later years. Concluding that the porous nature of the Mexican border posed a post–9/11 security threat to America, he had decided to pour all his efforts into doing something about it. That was his basic story, and it eventually became a kind of mythos unto itself.

He later told a reporter that he was dismayed by the way Hispanic gangs and students who couldn’t speak English were overwhelming Los Angeles schools, and at the same time he was becoming increasingly fearful of the prospect of a terrorist attack. “You could see it coming,” he said. “And then Sept. 11 hit, and that was it.”

The eliminationist impulse, in fact, gained fresh life in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, especially as the flames of fearfulness it produced were actually fanned rather than calmed by the American right, including the Bush administration itself. Professional fearmongers leapt onto the national stage to denounce fresh threats to national security, particularly seizing on the immigration debate, which was inflamed by claims that the insecure borders over which undocumented workers were flowing presented a prime opportunity (though the reality regarding those borders was largely obscured in the racial agitation that accompanied it).

The fearmongering occurred at all levels, from Pat Buchanan proclaiming that white American culture was about to be overrun by Latinos and other nonwhites, to Lou Dobbs parroting white-supremacist nonsense on CNN, to the entire bandwidth of nativists—including the usual suspects: VDare, the Federation for American Immigration Reform, Michelle Malkin, Juan Mann, Glenn Beck—demanding the immediate arrest and deportation of all 12 million illegal immigrants in America.

The 9/11 attacks convinced Simcox that he was right in his paranoid belief that Los Angeles was primed to become a terrorism target, and he freaked out. He called his estranged wife, Kim Dunbar, two days after the attacks and left a series of voice-mail rants about the Constitution and the impending nuclear attack on LA and how he intended to give his now-teenage son weapons training: “I will begin teaching him the art of protecting himself with

weapons,” he said. “I purchased another gun. I have more than a few weapons, and I intend on teaching my son how to use them. ... I will no longer trust anyone in this country. My life has changed forever, and if you don’t get that, you are brainwashed like everybody else.”

Simcox also called his son and ranted at him over the phone. Kim Dunbar recorded the conversations and submitted them in court proceedings asevidence of his mental instability. On the tapes, you can hear Simcox angrily challenge the boy to become “a man and a real American.”

“You better stop playing baseball, buddy, and you better do something real, ‘cause life will never be the same,” Simcox shouted. “I’m going to go down to the Mexican border and sign up for the government for Border Patrol to protect the borders of the country that I love. You hear how serious I am.”

Simcox indeed applied to join the Border Patrol but was rejected because, at age forty, he was too old. So he sold off his belongings and headed out to the Sonoran desert, camping for three months on the wild Arizona border and, he claimed later, witnessing all kinds of criminal border activity. He had his epiphany while camping at Organ Pipe National Monument and seeing drug traffickers. “At that moment, it clicked,” Simcox recalls. “The borders were wide open. Terrorists could come through.”

He eventually took up permanent residence in Tombstone, getting part-time work as a shootout-show actor—playing, aptly enough, one of the ex-Confederate “cowboy” gunmen who died in the showdown. (“I always got killed,” he wryly observed to a reporter.) Responding to an ad for an assistant editor at the Tombstone Tumbleweed, he was hired on the spot.

The Tumbleweed was that kind of paper. It didn’t really have much of a reporting staff, who covered local news only when they could get to it. It was run out of a little hole-in-the-wall office just off the town’s main street. And like a lot of such papers in dusty rural locales in 2002, it was having a hard time staying afloat, and its then-owner wasn’t merely desperate for an assistant editor—hell, he wanted a buyer. Sure enough, a few months after Simcox

had been hired, he cashed in his personal reserves—at one time, Simcox told reporters he had liquidated his son’s college fund, but in later versions it was his own retirement fund—and bought the paper for $60,000 in August 2002.

Simcox’s epiphany had given him a focus for his new career: within short order, the Tumbleweed became all about illegal immigration à la Roger Barnett and his nativist cohort, from whom he later acknowledged he had received his inspiration. The headlines shouted: “ENOUGH IS ENOUGH!

A PUBLIC CALL TO ARMS! CITIZENS BORDER PATROL MILITIA

NOW FORMING!”

He initially called it the Tombstone Militia but shortly changed its name to the much more broadly marketable Civil Homeland Defense Corps. At its first gathering in December, Simcox told reporters he expected about fifty people to participate, but only a handful, about five or six, actually showed. They may have been discouraged by the official resolution opposing Simcox’s plans for border militias passed by the city council of the nearest big town, Douglas. Mayor Borane authored the bill, writing: “Douglas is a bicultural and binational community, and the majority of its residents do not wish to encourage, be involved with or associate with these types of people, nor do they want our relationship with Mexico compromised by outside, xenophobic groups perpetuating hatred of humanity.”

When Simcox held a border-watch training event for his militia in January 2003, all of two volunteers showed up to take part. Four reporters were there to cover them. That was pretty much how it went for Simcox’s militia for a couple of years. The actual border watches would attract a handful of volunteers, many of them of dubious background at best. But there were always journalists of various kinds to be found: TV reporters, newspaper scribes, documentary filmmakers. They became Simcox’s target audience.

His attitudes about Latino immigrants were also unmistakable: “They’re trashing their neighborhoods, refusing to assimilate, standing on street corners, jeering at little girls walking on their way to school,” he told a nativist gathering.

Simcox similarly remarked of Mexicans and Central American immigrants: “They have no problem slitting your throat and taking your money or selling drugs to your kids or raping your daughter and they are evil people.”

He also told a documentary filmmaker: “I feel that the people that are coming across, invading this country, I think that they should be treated as enemies of the state. We need to be putting them in work camps. Anyone could walk through these borders of this country bringing bombs, chemicals, weapons of mass destruction. I think they should be shot on sight, personally.”

The border watchers he attracted shared those attitudes. In the same documentary, one of them—a middle-aged man named Craig Howard—sits out in the midday sun, watching a group of cows that have been wandering over the border from Mexico, where they eventually have to be herded back to their side of the line.

Howard drawls: “No, we ought to be able to shoot the Mexicans on sight, and that would end the problem. After two or three Mexicans are shot, they’ll stop crossing the border. And they’ll take their cows home, too.”

Then there was the leader of the Minutemen offshoot, Border Guardians, who offered suggestions via e-mails with neo-Nazis on how to eliminate Latino immigrants:

"Steal the money from any illegal walking into a bank or check cashing place."

"Make every illegal alien feel the heat of being a person without status. ... I hear the rednecks in the South are beating up illegals as the textile mills have closed. Use your imagination."

"Discourage Spanish-speaking children from going to school. Be creative."

"Create an anonymous propaganda campaign warning that any further illegal immigrants will be shot, maimed or seriously messed-up upon crossing the border. This should be fairly easy to do, considering the hysteria of the Spanish language press, and how they view the Minutemen as 'racists & vigilantes.' "

A San Diego Minuteman leader told a local newspaper: "If I occasionally let my language slip to a small group of people, that's my frustration with these people," he said. "I consider them less than human in the way that they conduct themselves as human beings, absolutely."

One of the border nativists’ more colorful figures was a bearded bicyclist named Frosty Wooldridge, who put on a “Paul Revere Ride”—a cross-country tour featuring motorcycles and bicycles, with pit stops in cities stretching all across the country that gave him an opportunity to preach against the ills of immigration—that was rife with the

kind of eliminationist rhetoric that was a common flavor at Minuteman rallies.

Wooldridge, author of a 2004 book titled Immigration’s Unarmed Invasion: Deadly Consequences, built his tirades around lurid tales of the evils brought to America by Latino immigrants, including diseases, crime, Santeria rituals, animal sacrifice, you name it.

Wooldridge indulged in a particular fetish about diseases, warning that “you’re breathing air that may be carrying hepatitis” simply by shopping at a Wal-Mart or going to a movie, and claiming that tuberculosis, head lice, and hepatitis were showing up in classrooms, and

that a deadly parasite that would destroy your heart was showing up in the nation’s blood supply. Wooldridge called all this the immigrants’ “disease jihad.”

“I don’t want to see my country taken over . . . and have them make the Southwest a slime pit Third World country like Mexico,” Wooldridge once proclaimed. He described California as a place “with its nightmare gridlock, schools trashed, hospitals collapsing, drug gangs and overall chaos generated by a Third World mob of illegal aliens.”

Just as he launched his tour that May, Wooldridge penned a classic eliminationist essay titled “A Day Without Illegal Aliens,” which concluded that ridding the nation of all twelve million of its undocumented workers would end a plague of crime and disease, but most of all, “America would not suffer balkanization, language apartheid, cultural apartheid, angry non-citizens, chaotic schools and bankrupted hospitals. Benefits gained include more jobs for Americans, peaceful communities, less drunks on highways, less burglaries, less rapes, greater honesty in business, fair wages paid to Americans and SO much more.”

In fact, virtually none of these claims are accurate. Numerous studies have concluded definitively that immigrants commit crime at much lower rates than native-born Americans, that they do not bring in diseases at an appreciable rate, that the taxes collected (as required by law) from their paychecks more than outweigh whatever social-benefit costs they incur, and that they remain eager adoptees of the English language. However, nativists like Wooldridge operated in a fact-free milieu in which emotions—particularly anger and resentment and fear—remained far more powerful and persuasive.

The Minutemen’s fractious behavior was in many ways a product of the combative personalities its core ideology attracted. The long history of nativist organizations in America is littered with the same story: gathered to fight the perceived immigrant threats of their respective times, and riding a wave of scapegoating and frequently eliminationist rhetoric, they all have in relatively short order scattered in disarray, usually amid claims of financial misfeasance and power grabbing.

“There has always been bickering among these types of organizations,” observed Christian Ramirez of the American Friends Service Committee, a human rights group affiliated with the Quakers that has condemned the Minutemen and their successors. “There is always someone trying to become the leader of the anti–illegal immigration movement, because it is such a fashionable thing. People are just fighting to see who is going to get more media attention.”

As it went national, the Minuteman movement attracted primarily angry white men who were fearful of demographic change, which played an outsize role in the organizations’ resulting volatility. Trying to rein them in was like herding cats. Big, angry cats with guns.

***

Around the fall of 2003, Simcox began corresponding with California retiree named Jim Gilchrist, who wanted to turn the vigilante border watch into a national movement. He even had a name for it: the Minuteman Project.

Gilchrist was a Marine veteran of the Vietnam War who tried his hand at newspapering after the war but wound up becoming an accountant before retiring at around 60. He was a fan of a California radio host named George Putnam, was also on the anti-immigration bandwagon, which made him a popular figure on the Los Angeles right-wing circuit. Simcox was a frequent guest. On an April 2003 show, Putnam made a fundraising pitch for Simcox, claiming that his “courageous stand” had brought the Tombstone Tumbleweed “to the brink of bankruptcy.”

Gilchrist had never been involved in any kind of political or other organizing in his life, but the alarmist hysteria of the nativist media narratives he consumed had convinced him that immigration was a real threat to the nation, and decided it was time to get into action. After catching Simcox on Putnam’s show in September, he came up with an idea: Why not take it national? Why not draw from a national volunteer base, instead of just relying on the locals?

He sent Simcox an email with his idea, suggesting that he could send out a national call for volunteers to a couple dozen folks across the country, maybe more, depending on what publicity they could rustle up. They would hold a monthlong watch on the border and make a statement. Simcox wrote back, enthusiastic. And they began organizing.

In late September 2004 Gilchrist and Simcox sent out their initial recruitment and fundraising email announcing the Minuteman Project: “Anyone interested in spending up to 30 days manning the Arizona border as a blocking force against entry into the U.S. by illegal aliens early next spring?” it asked. “I invite you to join me in Tombstone, Arizona in early spring of 2005 to protect our country from a 40-year-long invasion across our southern border with Mexico.”

It was to be a monthlong convergence of volunteers from across the country on the Arizona-Mexico border near Naco and Douglas in April 2005, intended as a citizens’ response to the “40-year invasion” of America by “illegal aliens.” The first emails went out to several dozen people, but the list kept growing. By mid-October the announcement had gone viral and spread nationally.

Though the Minuteman organizers vowed that 1,600 or more mad-as-hell volunteers had signed up for duty and that “potentially several thousands” would participate in the kickoff rallies during April Fools’ weekend, when the kickoff date arrived, turnout was an unmitigated flop—less than a tenth of the promised throngs showed up at the rallies. The entire Minuteman spectacle, indeed, easily qualified for that journalistic catchall phrase, “a fizzle,” but virtually none of the news media reported it as such.

Most of the reports showed people with binoculars and lawn chairs sitting in front of their motor homes and pickup trucks, keeping an eagle eye on a section of the border where immigrants rarely crossed anyway, and even fewer when the national media spotlight was focused on it. Late at night, there were disturbances; at one point, convinced their encampment was about to come under an imaginary nighttime attack from the MS-13 cartel, all of the border watchers went tearing around the landscape in their trucks, guns at the ready, spotlights everywhere. Fortunately, no one got shot.

The rifts in the organization showed up almost immediately. The “monthlong” border watch mostly dissipated after the first week, leaving mostly a handful of bellicose and paranoid conspiracists to cook together in the relentless sun. By the third week, only a raggedy remnant was hanging on. That’s when Simcox and Gilchrist first announced they were splitting operations: On Lou Dobbs’ CNN show, reporter Casey Wians announced the launch of “the next level” for the Minuteman Project: “the volunteer group today said it is planning now a major expansion along our southern border, and it plans to begin monitoring our northern border as well. The Minutemen are also launching a new operation to expose U.S. companies hiring illegal aliens.”

Then it was over to Wians, who dropped a bit of a bombshell—namely, that Jim Gilchrist was already leaving: Simcox, he said, “will begin consulting with organizers in California, Texas, and New Mexico to set up a Minuteman Project for the entire southern border, and they expect that to be operational by this fall” and that he would organize Canada border watches too, while Gilchrist “is going to be leaving active duty in Arizona to begin, as you mentioned, Lou, concentrating on employers who hire illegal aliens.”

The rift became open by December 2005, when Simcox and Gilchrist apparently decided — during a Conservative Political Action Committee gathering — to part ways, largely over how to handle the large sums of money the movement was attracting. So Gilchrist kept the Minuteman Project as his own, and Simcox fired up his own organization, the Minuteman Civil Defense Corps. By midsummer of 2006 the split had become public, and Gilchrist began openly distancing himself from Simcox.

By December 2007, the split was an open feud, especially after Gilchrist announced his endorsement of Republican presidential candidate Mike Huckabee; Simcox, who backed Ron Paul’s candidacy, retorted: “No, the Minutemen don’t support Huckabee. Jim Gilchrist supports Huckabee. This endorsement threatens to destroy Gilchrist’s credibility and the credibility of his organization forever.” Gilchrist replied by characterizing Simcox as part of a cadre of “professional extremists and charlatans.”

Indeed, one of Simcox’s subsequent fundraising schemes turned out to be a classic scam—one that foreshadowed Donald Trump: He proposed erecting a steel fence along rthe border, built by Minuteman volunteers, and began a national campaign to raise funds for it, which included erecting a “demonstration” fence that only ran about 200 yards along the border but made for great photo opportunities. The fence project, of course, was never constructed, though Simcox and his handlers managed to vacuum up millions of dollars in donations. The operation mostly ended up lining the pockets of his Beltway-based handlers.

***

The reality was that all the Minuteman factions attracted a bevy of scam artists and criminals. Foremost among these was a hairdresser and onetime Boeing line mechanic from Everett, Wash., named Shawna Forde, who first began showing up at Minuteman events in Washington state in the spring of 2006, organized (as promised) by Chris Simcox as proof that their Mexico-oriented border watches were not racist in nature. Simcox himself appeared before the Bellingham human-rights commission, denying that the movement condoned racists or extremists within their ranks.

Forde, who had a rap sheet as long as her legs that no one knew about, was a brassy personality who tried to assert herself as the press contact for the Washington state Minuteman detachment, gradually creating an internal uproar that erupted in her expulsion when she was caught rifling through the bedroom drawers of the group’s cofounder. She denied everything and convinced Simcox that she was being persecuted for being a woman; nonetheless, she shortly afterward announced she was creating her own border-watch group, and that she would be aligned with Gilchrist.

She named it Minuteman American Defense and set up shop near the border in Arizona’s Sonoran Desert. She attracted a number of participants in running “border watches” at various times in the spring and fall, and managed to attract film documentarians and news reporters.

Then, in June 2009, Forde was arrested and charged with masterminding the horrific murders of a 9-year-old girl and her father in the small Arizona border town of Arivaca, along with a white-supremacist cohort named Jason Eugene Bush and a local man, Albert Gaxiola, as part of her plan to create a border-militia compound. All three were convicted, and Forde and Bush wound up on Arizona’s Death Row.

After the arrests of Forde, Bush and Gaxiola, Forde’s former associates in the Minuteman movement fled from their onetime protégé. National leaders of the Minuteman movement — particularly Simcox and Gilchrist — hastily tried to put distance between themselves and Forde and her group. To this day, Gilchrist tries to claim that he had little to do with her.

Nor was Forde the only criminal in the ranks. In April 2012, one of Forde’s associates in the desert, a Tucson man named Todd Hezlitt, was arrested and charged with two counts of sexual conduct with a minor for an affair he had initiated with a 15-year-old girl from a local high school where he was an assistant wrestling coach. Two months later, he fled with the girl to Mexico, and he briefly became an international fugitive.

A few weeks after that, the girl turned herself in to the American consulate in Mazatlan. Hezlitt was caught a short time later and extradited. He eventually wound up agreeing to plead guilty to the sexual conduct charges in exchange for not being charged with kidnapping, and was sentenced to six years in prison.

Another violent incident from a former border watcher erupted in Arizona in May 2012 when Jason Todd “J.T.” Ready — a longtime leader of the state’s neo-Nazi National Socialist Movement, and an organizer of independent NSM border watches in Arizona — went on a shooting rampage at the home of his girlfriend.

Before committing suicide, Ready shot and killed his girlfriend, Lisa Lynn Mederos, 47; her daughter, Amber Nieve Mederos, 23; the daughter’s boyfriend, Jim Franklin Hiott, and Amber’s 15-month-old baby girl, Lilly Lynn Mederos. Investigators later found chemicals and military-grade munitions that apparently belonged to Ready at the residence.

The final coup de grace for the Minutemen came in 2014, when a Phoenix jury of nine men and three women convicted Simcox, 55, of two counts of child molestation and a charge of providing pornography to a minor. Simcox had been arrested the year before, charged with sexually assaulting his daughters and one of their young friends. Judge Jose Padilla later handed him a 19-1/2-year prison sentence.

The Minuteman brand name was finished. “A lot of people felt, well, you’re a Minuteman, you’re a killer,” Al Garza told Gaiutra Bahadur of the Nation, and then blamed not Shawna Forde or her enablers but the movement’s critics: “The name Minuteman has been tainted by organizations that didn’t want us at the border, that say we’re killers, that we’ve done harm.”

***

Though none of them use the Minuteman name any longer, a number of right-wing extremists have tried to keep border-vigilante operations running along the Mexico border. The most notable of these is Tim Foley’s Arizona Border Recon, which operates in roughly the same territory where Forde set up shop. Foley initially emphasized immigration, but later shifter to a strategy supposedly targeting drug-cartel operations.

In the meantime, the far right kept escalating its hatred of immigrants by reviving Minuteman-style vigilante groups on the southern U.S. border. Militia/Patriots also became increasingly involved in conspiracy-fueled resistance to Muslims and to refugee programs.

That was the environment in which Donald Trump announced his candidacy in June 2015, and immediately set an overtly eliminationist tone—describing Mexican immigrants as rapists and criminals—from the outset. (“They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”) It never ceased.

Throughout the 2016 campaign, the same kind of eliminationist rhetoric was directed at Muslim immigrants generally, as he talked about imposing a ban on immigration from Muslim nations. He also indulged in harsh rhetoric against refugees, warning that he intended to “send them back!” And of course, the centerpiece of his immigration was a big wall along the Mexico border—one that would put Simcox’s little fence to shame. He ordered construction to begin shortly after he won election, buoyed by the crowd chants at his rallies: “Build the wall!”

The apotheosis of Trump’s eliminationist rhetoric, however, was his regular reading of the poem “The Snake,” which depicts a “silly woman” who revives a dying viper (immigrants) only to be bitten by it in the end. It’s a classic depiction of humans as toxic vermin. Trump repeated his narration of the poem at almost every stop he made on the campaign trail in 2016, and he continues to repeat it even in 2024.

In addition to an anti-immigrant policy, he has notoriously used eliminationist rhetoric throughout his presidency, including the well-noted incident in which he sneered: “Why are we having all these people from shithole countries come here? Why do we need more Haitians? Take them out.” Then there was the time he notoriously sent out a tweet describing immigrants as “infesting” the country, as though they were lice and their nits.

In 2018, as the November elections approached, he began ratcheting up the fear around immigration issues by making the approach of a caravan of would-be asylum-seekers from Central America into a national security crisis. It wasn’t just Trump, either: Eliminationist rhetoric about the caravan spread everywhere, and not just on Lou Dobbs’s notorious fearmongering programs on Fox Business. It was the No. 1 story on Fox News. On Trump’s favorite show, Fox & Friends, Brian Kilmeade talked about the caravan as a disease vector.

The New York Times reported that Trump talked with staff about fortifying his border wall with a water-filled moat stocked with alligators and snakes, and he wanted the wall electrified, topped with flesh-piercing spikes. He also publicly suggested that soldiers shoot migrants if they threw rocks, but then backed off when told that it was illegal—as was his follow-up suggestion to shoot them in the legs.

Trump’s fearmongering over the caravan and Latino refugees, also classically eliminationist—calling them “invaders” and calling out American troops—was received ecstatically by extremists on the radical right. Unsurprisingly, it was precisely this heightened hysteria over the caravan that spurred the Pittsburgh synagogue shooter in October 2018, in no small part because of the latent anti-Semitism of the right’s immigrant fearmongering, especially their George Soros fetish.

Indeed, the pervasiveness of eliminationist rhetoric around immigration inspired several acts of mass violence. In August 2019, a Trump supporter named Patrick Crusius drove several hundred miles to a Wal-Mart in El Paso where he opened fire on unsuspecting customers, all of whom were Hispanic. He killed 23 of them and injured another 22.

He claimed his planned murders were “a response to the Hispanic invasion of Texas. They are the instigators, not me. I am simply defending my country from cultural and ethnic replacement brought on by an invasion.”

While Crusius had frequently praised Trump’s immigration policies online, a “manifesto” he published online sought to stave off any attempt to blame the president’s rhetoric for the attack: “I know that the media will probably call me a white supremacist anyway and blame Trump’s rhetoric. The media is infamous for fake news. Their reaction to this attack will likely just confirm that.”

A similar mass murder at a grocery store in Buffalo, N.Y., in May 2022 also was perpetrated by a man claiming that he was responding to “Replacement Theory”—the right-wing conspiracy theory that a globalist cabal is working to replace white people in modern society with brown-skinned immigrants. The incident demonstrated the flexibility of eliminationist hatred: The shooter, who took 10 lives—claimed that he targeted Black people because “they are an obvious, visible, and large group of replacers.”

Border vigilantism never stopped, either, though it continued to morph over the years. There were the United Constitutional Patriots, who in spring of 2019 set up a vigilante border-watch operation in New Mexico and began harassing asylum seekers while pretending to be Border Patrol officers. The leader of the UCP was arrested first for being a felon in possession of a firearm. Their spokesman was arrested a year afterward for impersonating a federal officer, then convicted and sentenced to 21 months in prison.

More recently, it’s shifted to clout-seeking harassment. In 2021, near Yuma, Arizona, the rabidly nativist, pro-Trump group AZ Patriots livestreamed its presence at a frequently used border crossing at the Morelos Dam. In the resulting videos, the group’s leader, Jennifer Harrison, could be seen harassing border-crossing asylum seekers, including children, as she shepherded them to awaiting CBP agents.

All of these Nativists are rabid Trump fans. Foley was a featured speaker at a couple of 2018 Trump rallies—first, a “unity” rally in Arizona in March, then at the “Mother of All Rallies” in Washington, D.C., in September. At the latter event, Foley told the audience, “It’s the worst of the worst” passing through the border in Arizona. What that entails, he said, was that he saw “Middle Eastern males,” on the border, and said the worst consequence was “All the diseases,” which were “transferred by all the children going into the schools.” He also called the border crossers “shitbags.”

After Trump’s November 2020 electoral loss, Harrison was one of the leading “Stop the Steal” figures protesting outside election-counting centers. Harrison also led a small delegation inside the building in the early moments of one protest, where video showed her demanding to be permitted to observe the count, and being denied.

Indeed, out of office, Trump’s rhetoric has reached bloodlust levels when he talks about immigration. He and his fellow Republicans continue to discuss Latino immigration—especially in the context of the flood of asylum seekers who have crowded border crossings in recent years—as an “invasion.” “We are being invaded by millions and millions of people, many of them criminals,” he told the crowd at a rally in Washington Township, Michigan, on April 2.

He laid bare the eliminationist impulse of this rhetoric in a December rally speech in which he decried the mere presence of immigrants:

They’re poisoning the blood of country. They poison mental institutions and prisons all over the world not just in South America, not just the three or four countries that we think about, but all over the world. They’re coming into our country from Africa, from Asia, all over the world, they’re pouring in to our country, nobody’s even looking at them. They just come in. And the crime is gonna be tremendous, the terrorism going to be.

When observers noticed how closely Trump’s rhetoric echoed that deployed by Adolf Hitler, he defensively explained at his next rally that he had “never read Mein Kampf.” This kind of evasive denial—someone does not need to have read Hitler’s ur-text to understand his ideology and rhetoric, particularly not if you keep a collection of his speeches on your bedstand—is a tell, the kind of “cleverness” that gives his white-nationalist and neo-Nazi defenders extreme joy.

Not to mention permission.